Pandemic Influenza 1918

Link Copied.When officials in Seattle announced a citywide lockdown, 15-year-old Violet Harris was overjoyed that she no longer had to go to school. I’ll say it is!” she wrote, excerpted at length in USA Today. “The only cloud in my sky is that the School Board will add the missed days on to the end of the term.” But as the reality of quarantine set in, Harris grew bored. Unable to leave home, she whiled away the hours by sewing a dress to wear to school when it reopened and experimenting with new recipes from the local paper, producing a particularly dreadful batch of fudge, half of which she ended up throwing out.

It seems that the full weight of the crisis dawned on her only when she received the startling news that her best friend, Rena, was sick with the Spanish Flu. A week later, after Rena had recovered, the two spoke on the phone. “I asked Rena what it felt like to have the influenza, and she said, ‘Don’t get it.’”. If history repeats itself, it’s only because human nature stays relatively constant.

The year 2018 marks the centenary of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Then, India had the largest number of deaths in any single country (10-20 million) as well as highest percentage of excess deaths (4.39%) in the world 1,2.The estimated total global death toll was 50-100 million.

Reading through newspaper articles and diaries written during the 1918 influenza pandemic, I felt an eerie flash of recognition. The dark jokes, anxious gossip, and breathless speculation reminded me of scrolling through Twitter over the past few weeks, watching people wrestle with life under quarantine by memeing through the crisis. Despite many similarities to the present moment, lockdown in 1918 was nevertheless a much lonelier experience than it is today. Lacking the many communication technologies that have allowed us to stay in contact with friends and family, early-20th-century Americans also struggled with the sudden loss of strong community ties, an experience that, to many, even outweighed the fear of a deadly and contagious disease. Many people quickly grew furious with the inconveniences of isolation.

“We were quarrentined sic on account of the Spanish Influenza and everyone is mad,” reads a written by a soldier stationed in South Carolina. Another soldier was that the quarantine prevented him from sending his family a Christmas gift.

Louis, Health Commissioner Max Starkloff made the controversial decision to order the closure of schools, movie theaters, bars, and—most devastatingly—public sporting events. The papers were in an uproar: “ INFLUENZA THREATENS FOOTBALL HERE,” the St. Louis Globe Democrat. “ MEASURES OF THE HEALTH DEPARTMENT CAUSING THE TEAMS MUCH UNEASINESS.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch dedicated article after article to the subject: “ QUARANTINE MAY LAST FOUR WEEKS; FOOTBALL SET BACK,” one headline. “ THE FOOTBALL GAMES ARE ALL OFF. THE SPANISH ‘FLU’ HAS PUT A DAMPER ON THE GRIDIRON,” another.

During the initial stage of the crisis, people worried loudly about the ways in which public-health measures were rupturing their daily routines, unwilling or perhaps unable to anticipate the more severe ramifications of the crisis. But in certain places, as the death toll began to rise, a sense of desperation set in, resulting in dark consequences for human relationships.Because of the isolated nature of quarantine, the 1918 pandemic was suffered largely in private.

Unable to lean on their friends and neighbors for support, people experienced the crisis alone in houses with shuttered windows. “I stayed in all day and didn’t even go to Rena’s,” Harris wrote in her diary. “Mama doesn’t want us to go around more than we need to.”These individual feelings of loneliness compounded, in some cases eroding once-strong community bonds. “People were actually afraid to talk to one another,” said Daniel Tonkel, an influenza survivor, during a 1997 for PBS’s American Experience.

“It was almost like Don’t breathe in my face; don’t look at me and breathe in my face, because you may give me the germ that I don’t want, and you never knew from day to day who was going to be next on the death list.”. Barry, the author of The Great Influenza, told me that feelings of loneliness during the pandemic were worsened by fear and mistrust, particularly in places where officials tried to hide the truth of the influenza from the public.

“Society is largely based on trust when you get right down to it, and without that there’s an alienation that works its way through the fabric of society,” he said. “When you had nobody to turn to, you had only yourself.” In his book, Barry details reports of families starving to death because other people were too scared to bring them food. This happened not only in cities but also in rural communities, he told me, “places where you would expect community and family and neighborly feeling to be strong enough to overcome that.” In an in 1980, Glenn Hollar described the way the flu frayed social ties in his North Carolina hometown. “People would come up and look in your window and holler and see if you was still alive, is about all,” he said. “They wouldn’t come in.”.

By December 1918, the number of new cases tapered off, and American society began to return, gradually, to normal. (“ PUBLIC WILL GET ITS FIRST LOOK AT 1918 FOOTBALL, WHEN BAN LIFTS, TOMORROW,” a headline in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.) However, the solitary aspect of the epidemic also affected the way that it was memorialized. As the disease stopped its spread, the public’s attention quickly shifted to the end of World War I, undermining the cathartic rituals that societies need to get past collective traumas.

In the decades after the sickness, the flu lodged in the back of people’s mind, remembered but not often discussed. The American writer John Dos Passos, who caught the disease on a troop ship, the experience in any detail.

“It never got a lot of attention, but it was there, below the surface,” Barry said.More than 80 years later, the novelist Thomas Mullen wrote The Last Town on Earth, a fictional account of the 1918 flu. In an after the book’s publication, Mullen commented on “a wall of silence surrounding survivors’ memories of the 1918 flu,” which was “quickly leading to the very erasure of those memories.” The historian Alfred W. Crosby deemed it “America’s forgotten pandemic.”. In many places, the loneliness and suspicion caused by the flu continued to pervade American society in subtle ways. To some, it seemed that something had been permanently lost.

“People didn’t seem as friendly as before,” John Delano, a New Haven, Connecticut, resident, in 1997. “They didn’t visit each other, bring food over, have parties all the time. The neighborhood changed. People changed.

Everything changed.”However, Barry reassured me, this was not universally the case. In his research, he found that communities came together in places where local leadership spoke honestly about the danger of influenza. “There was certainly plenty of fear nonetheless, you didn’t seem to find the kind of disintegration that occurred in other places,” he said. In cities where proactive public-health commissioners exhibited strong leadership, he argues in his book, people maintained faith in one another.Seattle Commissioner of Health J. McBride, for instance, firm public-health measures and even volunteered his services at an emergency hospital. In November 1918, he commended Seattle residents for “their co-operation in observing the drastic, but necessary, orders which have been issued by us during the influenza epidemic.” McBride’s actions may have been what allowed Seattleites like Violet Harris to remember the epidemic as a somewhat boring time.After six weeks of lockdown, public gathering spaces in Seattle finally reopened for business.

“School opens this week,” Harris wrote in her diary. Did you ever? As if they couldn’t have waited till Monday!”We want to hear what you think about this article. To the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Rivals of Aether Free Download PC Game Cracked in Direct Link and Torrent. RIVALS OF AETHER is an indie fighting game set in a world where warring civilizations summon the power of Fire, Water, Air, and Earth. Play with up to four players locally or up. CRACKED – FREE DOWNLOAD – TORRENT.

Haskell County, Kansas, lies in the southwest corner of the state, near Oklahoma and Colorado. In 1918 sod houses were still common, barely distinguishable from the treeless, dry prairie they were dug out of. It had been cattle country—a now bankrupt ranch once handled 30,000 head—but Haskell farmers also raised hogs, which is one possible clue to the origin of the crisis that would terrorize the world that year. Another clue is that the county sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards.

Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus. We cannot say for certain that that happened in 1918 in Haskell County, but we do know that an influenza outbreak struck in January, an outbreak so severe that, although influenza was not then a “reportable” disease, a local physician named Loring Miner—a large and imposing man, gruff, a player in local politics, who became a doctor before the acceptance of the germ theory of disease but whose intellectual curiosity had kept him abreast of scientific developments—went to the trouble of alerting the U.S. Public Health Service. The report itself no longer exists, but it stands as the first recorded notice anywhere in the world of unusual influenza activity that year. The local newspaper, the Santa Fe Monitor, confirms that something odd was happening around that time: “Mrs.

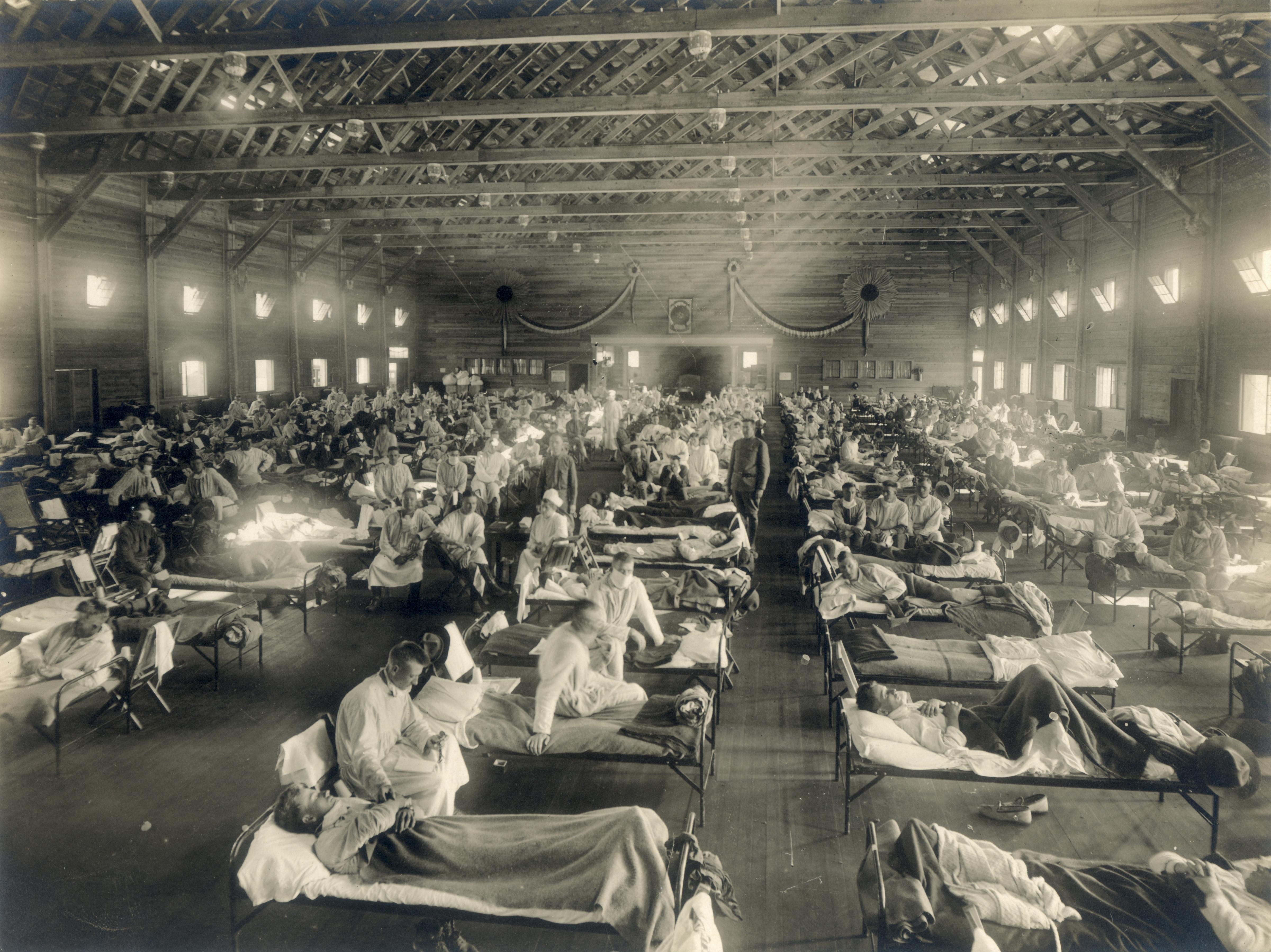

Eva Van Alstine is sick with pneumonia.Ralph Lindeman is still quite sick.Homer Moody has been reported quite sick.Pete Hesser’s three children have pneumonia.Mrs J.S. Cox is very weak yet.Ralph Mc- Connell has been quite sick this week.Mertin, the young son of Ernest Elliot, is sick with pneumonia.Most everybody over the country is having lagrippe or pneumonia.”Several Haskell men who had been exposed to influenza went to Camp Funston, in central Kansas. Days later, on March 4, the first soldier known to have influenza reported ill. The huge Army base was training men for combat in World War I, and within two weeks 1,100 soldiers were admitted to the hospital, with thousands more sick in barracks.

Thirty-eight died. Then, infected soldiers likely carried influenza from Funston to other Army camps in the States—24 of 36 large camps had outbreaks—sickening tens of thousands, before carrying the disease overseas.

Meanwhile, the disease spread into U.S. Civilian communities.The influenza virus mutates rapidly, changing enough that the human immune system has difficulty recognizing and attacking it even from one season to the next. A pandemic occurs when an entirely new and virulent influenza virus, which the immune system has not previously seen, enters the population and spreads worldwide. Ordinary seasonal influenza viruses normally bind only to cells in the upper respiratory tract—the nose and throat—which is why they transmit easily.

It goes: Down, Down, Up, Up, Down, Up. Open it and pull the correct switches down to match the drawing in the book. The eyes of ara ceiling puzzle. Then read through the MIA Generator Operator’s Manual on the desk to get a clue. There’s a yellow fuse box above the desk. Do the same for the one on the wall and the one on the generator.

The 1918 pandemic virus infected cells in the upper respiratory tract, transmitting easily, but also deep in the lungs, damaging tissue and often leading to viral as well as bacterial pneumonias.Although some researchers argue that the 1918 pandemic began elsewhere, in France in 1916 or China and Vietnam in 1917, many other studies indicate a U.S. On October 16, 1918, a letter carrier in New York City makes his rounds wearing a mask for protection.(National Archives)Seasonal influenza is bad enough. Over the past four decades it has killed 3,000 to 48,000 Americans annually, depending on the dominant virus strains in circulation, among other things. And more deadly possibilities loom.In recent years, two different bird influenza viruses have been infecting people directly: the H5N1 strain has struck in many nations, while H7N9 is still limited to China (see “”). All told, these two avian influenza viruses had killed 1,032 out of the 2,439 people infected as of this past July—a staggering mortality rate.

Scientists say that both virus strains, so far, bind only to cells deep in the lung and do not pass from person to person. If either one acquires the ability to infect the upper respiratory tract, through mutation or by swapping genes with an existing human virus, a deadly pandemic is possible.Prompted by the re-emergence of avian influenza, governments, NGOs and major businesses around the world have poured resources into preparing for a pandemic. Because of my history of the 1918 pandemic, The Great Influenza, I was asked to participate in some of those efforts.Public health experts agree that the highest priority is to develop a “universal vaccine” that confers immunity against virtually all influenza viruses likely to infect humans (see “”). Without such a vaccine, if a new pandemic virus surfaces, we will have to produce a vaccine specifically for it; doing so will take months and the vaccine may offer only marginal protection.Another key step to improving pandemic readiness is to expand research on antiviral drugs; none is highly effective against influenza, and some strains have apparently acquired resistance to the antiviral drug Tamiflu. Magisterial in its breadth of perspective and depth of research and now revised to reflect the growing danger of the avian flu, 'The Great Influenza' is ultimately a tale of triumph amid tragedy, which provides us with a precise and sobering model as we confront the epidemics looming on our own horizon.Then there are the less glamorous measures, known as nonpharmaceutical interventions: hand-washing, telecommuting, covering coughs, staying home when sick instead of going to work and, if the pandemic is severe enough, widespread school closings and possibly more extreme controls. The hope is that “layering” such actions one atop another will reduce the impact of an outbreak on public health and on resources in today’s just-in-time economy. But the effectiveness of such interventions will depend on public compliance, and the public will have to trust what it is being told.That is why, in my view, the most important lesson from 1918 is to tell the truth.

Though that idea is incorporated into every preparedness plan I know of, its actual implementation will depend on the character and leadership of the people in charge when a crisis erupts.I recall participating in a pandemic “war game” in Los Angeles involving area public health officials. Before the exercise began, I gave a talk about what happened in 1918, how society broke down, and emphasized that to retain the public’s trust, authorities had to be candid. “You don’t manage the truth,” I said. “You tell the truth.” Everyone shook their heads in agreement.Next, the people running the game revealed the day’s challenge to the participants: A severe pandemic influenza virus was spreading around the world. It had not officially reached California, but a suspected case—the severity of the symptoms made it seem so—had just surfaced in Los Angeles. The news media had learned of it and were demanding a press conference.The participant with the first move was a top-ranking public health official.

What did he do? He declined to hold a press conference, and instead just released a statement: More tests are required. The patient might not have pandemic influenza. There is no reason for concern.I was stunned.

This official had not actually told a lie, but he had deliberately minimized the danger; whether or not this particular patient had the disease, a pandemic was coming. The official’s unwillingness to answer questions from the press or even acknowledge the pandemic’s inevitability meant that citizens would look elsewhere for answers, and probably find a lot of bad ones. Instead of taking the lead in providing credible information he instantly fell behind the pace of events.

He would find it almost impossible to get ahead of them again. He had, in short, shirked his duty to the public, risking countless lives.And that was only a game.